Few architects have had as much international impact on architecture as Moshe Safdie. His practice Safdie Architects has been progressing architecture and changing skylines across the globe for over 50 years. Recently Safdie was a keynote speaker at the Australian Institute of Architects National Conference, which was hosted on the Gold Coast. It is an absolute privilege to have been able to interview Safdie during his Australian visit.

Michael Smith – So, let’s start at the beginning of your career. You worked with Louis Kahn and I was just wondering, what was he like and what did you take away from that experience?

Moshe Safdie – I was very young. I’d only worked briefly for my Professor, Sandy Van Ginkel in Montreal. I arrived at Kahn’s office, staffed by people who had studied and worked with him for some time. It was quite an intimidating moment to start with, but I found out quickly that I was working with him hand-in-hand on projects. At the time, I was very argumentative and opinionated. For example, while I obviously admired what he did because he was the only architect I wanted to work for, I wondered why, for a project in India, he was romanticising local construction methods, and why not prefabrication and the new modern ways? This was especially evident as we worked on the Institute of Management in Ahmedabad. In retrospect, he was absolutely right. It took me years to appreciate that.

What I learned from Kahn is how to practice architecture. My office today is very much in the image of Kahn’s practice. I even learned to use charcoal from him as a kind of fluid way of thinking.

Above all, I learned to stay focused on to details and the systems. Determining that systems were the key issue. You could not conceive architecture without conceiving the systems, and working with the engineers from day one. During construction is where you make some of the most important decisions. These principles of being an architect I learned from Kahn.

Habitat 67 View from Courtyard image by Timothy Hursley

Michael Smith – It’s now been over 50 years since Habitat 67 opened. Since, that time Brutalist architecture has become one of the most controversial periods of architectural history. Looking back on this project and the Brutalist era, are there lessons that we are still to learn from this period?

Moshe Safdie – I should make one important distinction: I don’t think of Habitat as Brutalist at all. In fact, at the time people were doing what has come to be known as Brutalist architecture, the idea was utilizing a rough concrete. I think of the works of Rudolph with the corduroy concrete, and his followers, for example, or Le Corbusier in India with really rough concrete. My efforts in Habitat were to make the concrete look as finished and smooth as possible. I went to precasting and carefully sandblasted the surfaces, with the hope that they would look like limestone. I had no interest in the ruggedness and spontaneity of Brutalist construction.

While it coincides with the same time period of Brutalism, conceptually Habitat was not that at all. And I don’t think any of my buildings that followed were anything but an attempt to provide a comfortable, high finish. I think people want to feel and touch architecture, and concrete that cuts their hand is the opposite.

Looking back on Habitat, I think in some ways it was a fairy tale. Now that I’ve been in practice 50 years, I don’t know for the life of me how I got away with it. I don’t know how I managed to convince three levels of government, at age 25, having never built a building, that Habitat was a sound idea — and to then fight it through the system. I sometimes watch some interviews and films from that era and I don’t see the secret. I must have been totally convinced about things in the way that was contagious. The structure is very sophisticated, and I did it with an office of 30 or 40 people, all of whom had as little experience as I did. The only one who had more experience was the structural engineer August Komendant.

Michael Smith – One the recurring themes from the 2018 Australian Institute of Architects National Conference has being a concern around the globalisation of architecture, leading to the homogenization of buildings and cities. How serious do you think this issue is and what do we need to do about it?

Moshe Safdie – I think it’s a central issue for architecture. Today, with only 40 minutes for my talk, I had to pick and choose about what to emphasise. I talked mostly about megascale buildings that we are doing dealing with densification. Another talk I could’ve easily given is about our institutional work, where I try to capture the spirit and culture of the place and particularly challenging sites. Projects with strong symbolism, such as the Khalsa Heritage Centre (the national museum of the Sikhs) in India or Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem, are examples where the symbolic overtones are intimately tied to their locale and people. I am interested in how to you make architecture that belongs to its site and program, which immediately means that concepts cannot be exported from one place to another. Many architects have developed a personal language of forms and shapes and structures and materials, and take it from place to place, which I do not believe achieves a design specific to place.

Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum Exterior image by Timothy Hursley

For a long time, I was confusing critics because they couldn’t find the common denominator style between my projects in India, Jerusalem and Washington or San Paulo. I think that is because I’m committed to finding the essence of place in the architecture, which is a kind of antithesis of globalisation. How many architects are doing projects in various parts of the world, which are instantly recognisable, but not particular to their setting?

Michael Smith – I suppose that also reaches back to your time with Louis Kahn?

Moshe Safdie – Absolutely. There are others of my generation who are occupied with this question. Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers are examples. But I think that the thrust of current avant-garde thinking is not interested in the essence of place.

Michael Smith – Your talk at the conference was largely about megascale projects, the most famous of which is Marina Bay Sands, with its horizontal bridging park at the 57th floor. With these horizontal decks, how publicly accessible are they? And are they typically in private ownership or government ownership?

Moshe Safdie – Well we must separate between the current situation and the conceptual proposition. Currently the projects we are doing that contain what has been called a horizontal skyscrape are primarily private. The skyscraper term is probably more accurate than deck or street, because there is so much more program in these examples. The Raffles City project in Chongqing, China and another mixed-use project in Seoul, South Korea, as well as Marina Bay Sands, each have components that are publicly accessible, but not all of the space is free. I have yet to achieve a space that is truly public.

Aerial View of Marina Bay Sands courtesy of Marina Bay Sands

In Chongqing, the whole roof of the podium is a public park, that’s not at the 50th level, it’s the fifth level of the podium. In the long-term I can envisage that there’s a whole complex, in which the zoning determines that the 25th floor or 30th floor will be a public deck/ street that connects all development in the district, and that you are mandated to connect to it and that it is a public right of way. I think that’s where we’ll really start making headway. We will have several levels for urban life. With the ground level compromised by traffic and access and some daylight restrictions, public streets at the 25th or 30th level can be endowed with both views and lots of amenities. And, the opportunity is for the start of organising high rise construction in a way that’s much more liveable, more than just individual disconnected towers.

The key is to make the quantum jump from individual towers, which by definition are self-contained entities with vertical circulation, to a circulation system in the city, which is grid-like in three dimensions. This system might have certain paths horizontally, and some vertically, but the idea is that they all intersect and are public.

Michael Smith – The role of governance of those spaces is critical.

Moshe Safdie – That’s the toughest thing to overcome now: to get municipal authorities and beyond to think three-dimensionally, and to zone accordingly. The private projects I’m involved in are pilot projects towards this three-dimensional thinking.

Raffles City Chongqing Conservatory image courtesy Safdie Architects

Michael Smith – Do you see in the future as the century progresses, do you think the cities are going to become more three-dimensional in their planning?

Moshe Safdie – It’s inevitable. I think it will become the norm because it solves a lot of problems. We lament and miss 19th century urbanism, which is non-existent in the new megacities. We enjoy Venice and Paris, but miss them in the contemporary context. To create the level of intimacy and interaction I am talking about must engage this matrix of movement. As density increases and there is more complex movement in the city, you can create more options. You still have to concentrate the paths, because that’s the way public space works, but it solves a lot of issues and creates a lot of opportunities if you go 3D.

Michael Smith – One of the forces in the 21st century is that multi-national corporations are becoming increasingly powerful, sometimes more powerful than governments. Organizations like Google and Facebook have almost infinite resources and access to the latest technology and data. Do you see a role for these companies in city-making, or is that a recipe for disaster?

Moshe Safdie – First, we must make a distinction between systems and networks, and the technologies that facilitate it, and between the regulatory systems that govern them. Somebody has to create a framework and an ordered system for urban development. This cannot appropriately be provided by mega corporations, who are too self-serving and with self-centered agendas. In spite of bureaucratic inefficiencies, I see no other solution than some public authority. At its best, I look at Singapore and the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). There are other bodies emerging in various cities and municipalities who have the courage to think through the ultimate diagram and work with the best minds in the profession. I don’t think that bureaucracy can ever can have all the answers internally, it’s got to draw on the best brain power from the profession.

Specific issues like driverless cars can be solved by entities such as Google or Uber, or technology such as elevators that move vertically as well as horizontally. But the ordered system of urbanism needs a different model of collaboration.

Another danger in globalisation thread is branding. The fact that you walk into the town centre in Robina, Queensland and it’s all the same retailers – Zara, Vuitton or Chanel, and it looks like the same brand in every corner of the world. Maybe the scales of economy and promotion are inevitable, but at least you would like to hope that the grassroots localised merchants, craftsmen, farmers, who offer their wares and merchandise have the same opportunity. On a recent trip to France, walking around Bordeaux and Paris, I was struck by the variety of shops and offerings, reflecting the small, family owned merchants. It was such a pleasure to see. They still have the megabrands, but it is balanced by the family-owned businesses, and the farmers who still bring in their wares to the Saturday market.

Architecture is for everyone.

Click here to continue to part two of the discussion with Moshe Safdie.

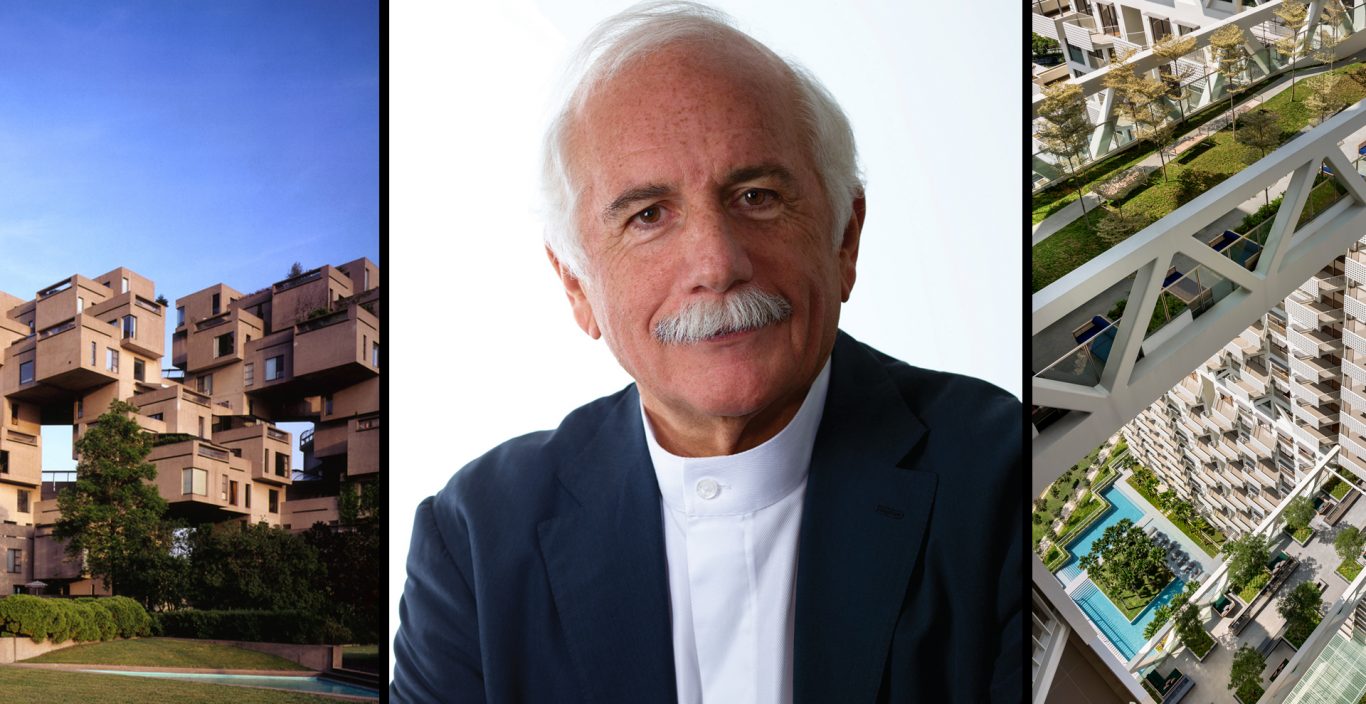

Lead image credits (left to right):

Habitat 67 View from Courtyard image by Timothy Hursley

Moshe Safdie portrait, by Stephen Kelly

SkyHabitat, View from Bridge to Ground image by Edward Hendricks

Contact Us

Feel free to contact us with questions or feedback:

Latest Post

- A crisis of trust February 10, 2020

- The Square and the Park. October 28, 2019

- Fixing The Building Industry – A Wishlist September 12, 2019

- 2019 NATIONAL CONFERENCE DAY 2 June 24, 2019

- 2019 National Conference Day 1 June 22, 2019

Leave a Reply