Canberra is a city designed as a symbol, a focal point of the Australian nation which is laced deeply with meaning. A designed landscape of view lines and stone monuments, flagpoles and buildings of national significance. It is the place where the deeper symbolic meanings of architecture can be more easily read and understood by the public at large.

The democratic and inclusive symbology of Canberra as our capital perhaps began with the idea that the capital is neither Sydney nor Melbourne but a compromise between the two. The masterplan of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahoney Griffin set in place a framework in which the symbols and values of a nation could be enshrined. To set this up, the governmental functions were imagined within a parliamentary zone specifically set apart from the civic functions of the city. This separation was made via a new lake which would provide a critical distance from which the Nation’s symbols could be observed. This was not about isolation but about reinforcing the higher purpose of the city.

The controlled geometric vistas also emphasised the parliamentary zone but at the same time connected it with the natural landscape. The strong visual relationship to the Australian War Memorial was first conceived as a connection to Mount Ainslie. This idea was to connect the great forces upon our world – nature and democracy.

A great successes of the masterplan is the ability for it to be developed in order to reflect the nation’s identity as it passes through history. As our national identity changes, so too does the built representation of it. Therefore, by examining our built capital, we can determine what values the Government and by extension, the Nation, holds dear.

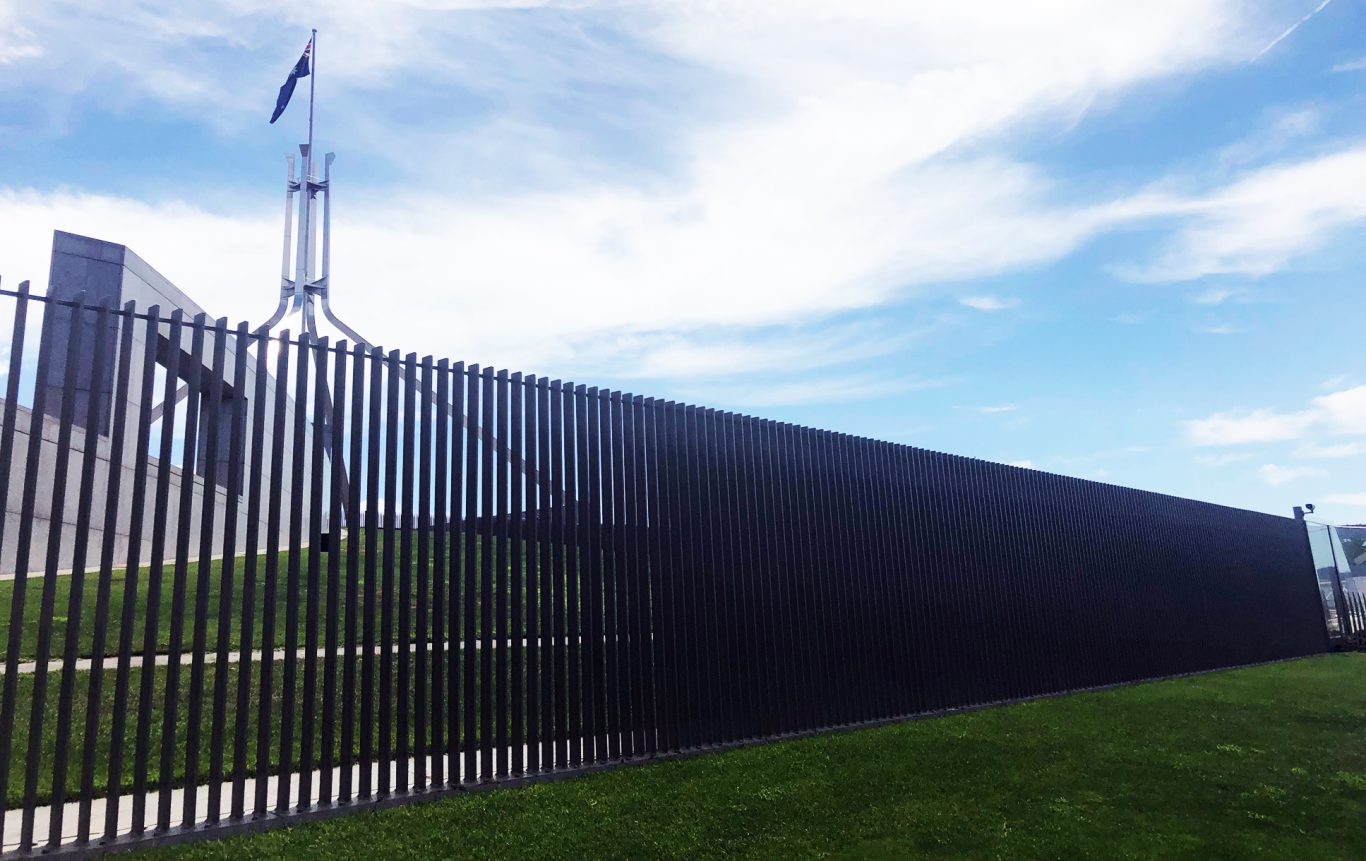

One obvious example is the security fence across Parliament House that either represents our capitulation to terrorism, or embracement of pragmatism, depending on your viewpoint. As our fear of terrorism grew, successive governments have changed laws, reduced freedoms and increased security budgets. Emotion led to discussion, which led to policy, which then then inevitably led to representation in physical form.

This cycle is now beginning again with the political discussion surrounding of our colonial and wartime history. The conservative federal Government has dedicated $50 Million to further memorialise Captain Cook whilst The Prime Minister Scott Morrison has also forcefully insisted on councils celebrating Australia Day on January 26th and even a dress code for citizenship ceremonies. The Governments agenda of nationalism and the celebration of white settlement is currently in full force.

Strangely, our Governments fetish for select portions of Australian History is actually making our history more confusing and less known, despite the expenditure of hundreds of millions of dollars. For example the new memorial at Villers-Bretonneux in France is named after Sir John Monash. This is a confusing choice, as Monash had nothing to do with the Australian counter attack in 1918 that is memorialised by the building. The potential for misunderstanding our history, was played out by none other than Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, who at the opening of the building made a speech praising Monash’s involvement in the event.

Seemingly learning nothing from even recent history, Prime Minister Scott Morrison has instructed that the replica of Captain Cook’s Endeavour trace the journey of….. Matthew Flinders.

As we should expect from this national discussion of values and identity, Australia’s capital will eventually have this discussion set in concrete. This has begun to happen at Anzac Hall, an award winning extension to the Australian War Memorial by Architects Denton Corker Marshall. Last year it was announced that this building is set to be demolished and replaced with a new $498 million dollar memorial building. This decision is extraordinary for its waste and for its expense. The existing Anzac Hall is fit for purpose, beautiful and less than 18 years old. It’s only deficiency is that politically it cannot visibly, symbolically and financially connect the Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison Government with the ANZAC story. Therefore our capital will expand the National acknowledgement of our military further, hopefully without falling into glorification.

Sadly even within the framework of supporting our military there are much better ways to spend a lazy half billion. Perhaps improved mental health facilities and programs for ex-servicemen and women could have been an alternative for these taxpayer dollars.

With the history wars in full gear it is perhaps a surprising point to find optimism. However with a Federal election just around the corner and with a real possibility that the Government will change, there is an opportunity to pick up a discussion about a more substantial and purposeful change to our capital.

In 2017 at the First Nations Constitutional Convention in Uluru, the Uluru Statement From The Heart was released. It asks for constitutional reforms that would give a voice to the people of the First Nations.

‘With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.’

ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

In Canberra, our physical manifestation of all that our nation holds dear, the representation of the First Nations is hideously deficient. Nowhere is the sovereignty of the first nations, which was never ceded or extinguished, recognised appropriately.

In the absence of a prominent and comprehensive national indigenous institution, a ‘tent embassy’ has been occupied by indigenous peoples outside Old Parliament House for the last 45 years. This occupation is a desperate attempt for indigenous recognition and for political attention to the plight of indigenous people. From its beginning, those occupying the space understood the symbolic importance, even though our successive elected governments have largely ignored them. Now with the loud and clear ask for indigenous constitutional recognition, we need to recognise the First Nations in our national buildings as well. Just as the High Court is both constitutionally enshrined and set in concrete, so too should a centre for the first nations that can permanently and symbolically represent 60,000 years of culture that preceded the British invasion.

The form, structure, program and construction of this new building would need to be determined with intense and integrated dialogue with indigenous communities. Potentially this new facility could house a very large agenda that encompasses the functions of a memorial, a museum, an education facility and a residential component that would enable a more permanent and comfortable occupation of the site. Most importantly it could also be the home of the national First Nations representative body which under the Uluru Statement would advise the Parliament. This is of course unless Parliament House were adapted to include this chamber, as it is possible to do.

As Robin Boyd once pointed out that “There can be few other nations which are less certain than Australia as to what they are and where they are”. If as a nation we can acknowledge, embrace and memorialise accurately all aspects of our history, including our indigenous history, we will begin to understand more fully who and where we are. Maybe then we might even understand collectively why Australia needs to move its national day.

Architecture is For Everyone

Contact Us

Feel free to contact us with questions or feedback:

Latest Post

- A crisis of trust February 10, 2020

- The Square and the Park. October 28, 2019

- Fixing The Building Industry – A Wishlist September 12, 2019

- 2019 NATIONAL CONFERENCE DAY 2 June 24, 2019

- 2019 National Conference Day 1 June 22, 2019

Leave a Reply