Recently, the current Victorian Planning Minister Richard Wynne made a highly unusual decision to reject a recommendation from the Heritage Council of Victoria to list and protect the APM Boiler House in Alphington. To unpack this unprecedented decision and find out more about the APM Boiler House, we caught up with heritage consultant and architectural historian Rohan Storey, who is a strong advocate for Victoria’s heritage, having worked for the National Trust for 20 years.

Michael Smith – Why is the APM Boiler House building a significant piece of Melbourne’s architecture?

Heritage Consultant Rohan Storey

Rohan Storey – A long time ago, I knew that it was reputed to be the first full scaled curtain wall in Melbourne. First all glass curtain wall. And, when the site was up for redevelopment, a heritage report was done which examined many aspects of significance, which found that yes, it was the first large scale all glass curtain wall in Melbourne, 1954, and designed and started construction 1951. And apart from that, it’s also stylishly modern and notably so for an industrial building.

MS – What was the building’s purpose in its heyday?

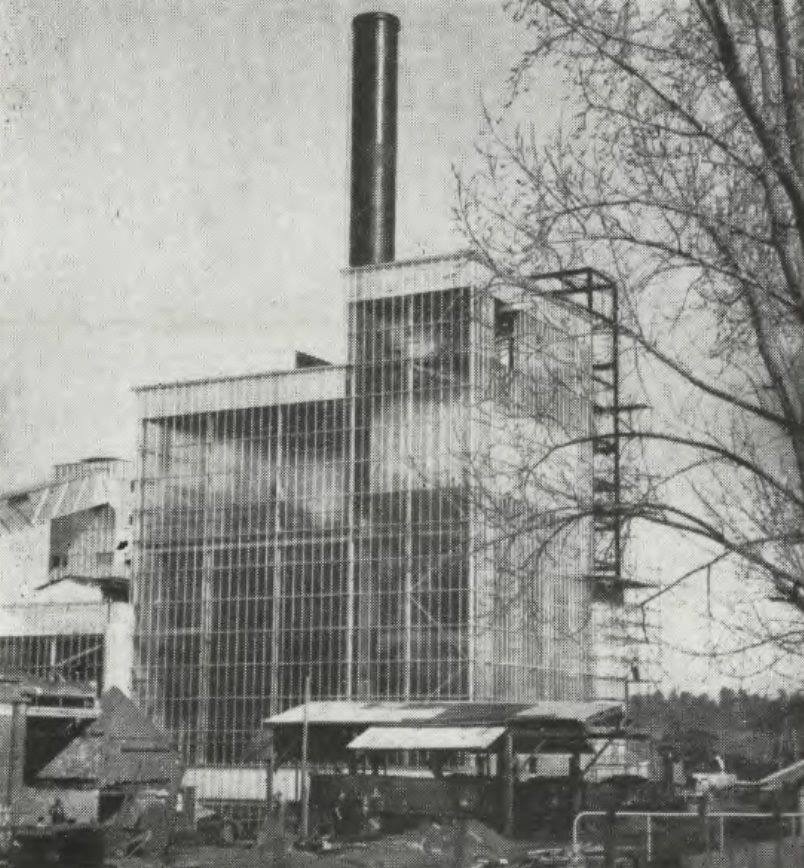

RS – It was built as a power station essentially, for the gigantic paper-mill on the site. There is a 1920s one next to it and this was part of a post-war expansion, like so much of Melbourne. Post-war Melbourne’s growth was partly built on enormous factory complexes, mostly in the outer suburbs and this one was increasing the size of one that already existed in an inner suburb. And, it was designed by notable architects as many industrial complexes were at the time. But this is one of the most unusual ones in that it was an actual industrial process building that was also architecturally notable. Most of the complexes, the big shed parts, were just sheds. Usually the architects would put all their effort into the administration building at the front. Like, the fantastic wavy-roofed Peters ice cream building in Mulgrave. Whereas the buildings themselves behind, where the ice cream was actually made were nondescript. This one was a power house, which had a coal fired furnace, which ran turbines, which were in the turbine hall next door. So it had coal coming in one end, going through the process of being burnt and turning water into steam, which ran electric dynamos which ran the plant. And coming out as ash and smoke and power at the other end. And all of that was on display, because both the turbine hall and the boiler house included large areas of translucent glass. So it would have glowed on a winter evening, illuminating the industrial process itself.

APM Boiler House

(source: Rohan Storey)

MS – The developers of the site are currently proposing to transform it into a new 21st century housing development. For those who perhaps haven’t been following so closely, how this transpired?

RS – I suppose the first part was APM, later Amcor and still known as Amcor, closing the site and selling it. And, at about that time, Yarra City Council required a master plan, rather than just waiting for them to propose something out of the blue.

So, there was a long process of master-planning for the site, which involved recommended height limits of various parts and percentages put aside for open space, and the ideas of ESD (Environmentally Sustainable Design), a community centre of some sort and possibly a primary school, and of course some retail.

MS – And, part of this master plan included the retention of this boiler house because of its heritage value?

RS – Yes, as part of the master-planning for the site, the developers engaged heritage consultants who examined the whole site and rated the various buildings, of various levels of significance, which boiled down to three “significant” buildings, the remnants of some tanks, and one “contributory” building. And this powerhouse is one of the three significant ones. The adjacent 1920s powerhouse is the other one. And the other “significant” one was the great big brick buildings along Heidelberg Road that everyone probably knows, from the ’60s, which were also going to be kept originally.

So, the heritage consultants noted these buildings as important and they should stay, and gave reasons why they should stay. But, when the master plan came up to Council, suddenly, for those few of us from Heritage Land who were interested … suddenly, Council passed a resolution to approve the master plan with the modification that it would include the demolition of the power house. Even though it was heritage listed at the local planning scheme level.

Straight after that, it was nominated to Heritage Victoria, I think as a joint effort of a number of different parties, including the National Trust. Heritage Victoria then did their assessment and they said, “Yes.” And advertised it in the normal way.

Then at some point during the advertising, or possibly at the end of the advertising period, the Minister used his powers to “call in” the decision, which means that the appeal went directly to his office, rather than the independent body called the Heritage Council, which normally hears appeals.

The Heritage Council did in fact take all the submissions and write up a report, in which they agreed it should be listed, which they sent to the Minister. So Heritage Victoria and the Heritage Council report both recommended that it should be added to the Victorian Heritage Register.

MS – And then, subsequent to that, the Planning Minister Richard Wynne has decided not to list the boiler house. Citing I believe amongst other things, that it is, to his mind, an ugly building.

RS – Yes, it was very value-laden – his press release described it as an “eyesore” and it was “time for it to go” and quoted the local resident’s notion that, “it was hated.” This was a phrase that was used by one of the local residents who made a submission to the Heritage Victoria process. There were four or five submissions from the local lobby group, who were all basically saying, “it’s ugly, therefore it should be demolished.”

It’s ugliness by association. If it’s industrial, it must be ugly.

MS – This is a common theme with a lot of significant heritage buildings. We’ve seen it up in Sydney with the Sirius building. A lot of the political support to demolish the building has come from those claiming it to be an ugly eyesore. When I say political support, mainly from the politicians proposing it in the first instance, rather than community or anyone else. But, there is obviously a bit of a tension between beauty and heritage when it comes to the built environment. And undoubtedly, having a beautiful built environment is a good thing. So, I suppose, playing the devil’s advocate, “Why is it a problem to demolish ugly buildings?”

RS – The problem is the definition of ugly changes with time of course. In the 1960s, everything Victorian was considered ugly, and they were demolished left, right and centre. And now of course, you wouldn’t think of touching any of them, and now, we’ve moved onto Art Deco. Any building with even a hint of Art Deco is generally considered a fine and wonderful thing.

But, modern architecture is still struggling to be accepted as heritage. Though there is a large and growing body of people who are uncritically adoring of modernist buildings and modernist architecture and modernist houses. Especially with social media you can see this happening, but also articles in newspapers, and even real estate sales pitches sometimes are about what a wonderful bit of modern architecture this 1960s house might be, but when it comes to industrial architecture, basically … industrial plus modern equals ugly for some people.

“Actual buildings are much better interpreters of history”

So, it’s not so much in this case really that it’s a modernist building that makes it ugly, just that it’s a factory and that, those that think that it’s ugly think that all factories are ugly. At least the ones that aren’t charming red brick Victorian factories.

MS – Broadening it out, in addition to the building’s significance from an architectural point of view, is it also not critical for the identity of a place to have the story of that place carried forward for future generations?

RS – Well, yes that’s the one function of heritage is to live as a reminder of the past and past practices and places and what was there before. But, when it comes to large complex industrial sites, they tend to get wiped away almost completely.

And in this case, I went past not long ago and the demolition of the ’60s buildings on Heidelberg Road was nearly complete, leaving a huge empty site, with one small 1930s red brick building in the middle, small part of the “contributory” building, and the pair of power houses… and if the ’50s powerhouse is demolished, there will only be two buildings left standing, and the tank bases. That’ll be all that is left of that enormous site and its history.

So yes, keeping some remnants and certainly all the most significant parts, is always important when dealing with a site that has some significance. Some places that have not much significance, you can demolish the lot, but industrial sites are ones where it would be best to keep something. And contrary to the Minister’s statement that the history of the site “will be served” by, I don’t know what, like plaques and street names , maybe interpretive art or something. The actual buildings are much better interpreters of history.

MS – How would you like to see the site developed going forward? If you were suddenly granted to be Planning Minister for a day? Or indeed, if you were the developer who’s proposing to do this development, what would you like to see happen on this site?

RS – I can appreciate the developer may find it very difficult to keep the 50s power house because it’s a complex building to remediate. Not because of the asbestos, just because it’s a complex bit of machinery wrapped in architecture. In an ideal world I’d do what they do in Germany, where they treat their industrial heritage with respect and they get grants to keep and remediate and retain important places like this. So, a developer would be allowed to build a lot of stuff, but at the same time, the important bits would be retained and probably given over to public uses

So, in this case, the ideal situation would be that the two power houses and the 30s building would be kept, and they would be used for community purposes and then the developer would be allowed to do their 14 stories over here and five stories over there and townhouses over there.

MS – I suppose a frustrating thing about this story so far is that the site was sold with the master plan, that included the retention of these buildings. So, the developers, theoretically, should’ve been able to price that in as the amount that they bid for the site because there would be a certain amount allocated to retaining these buildings. And, I suppose one has to ask the question, and maybe they did price that in, and are they just pocketing the money?

RS – I’m sure they are very happy with the Minister’s decision but in this case, surprisingly, it wasn’t a decision made at the behest of the developer, though I’m sure the developer would have had a meeting with the Minister. But the demolition of this particular building was very much the focus of a local lobby group who really focused on it as ugly and horrible, and an eyesore and much better to replace it with apartments. Even though, they’re probably also equally shocked about the scale of the development and what is actually going to happen there.

The retention of the buildings was in the master plan, though there were a few caveats in there saying you know, ‘if possible’, ‘where feasible’, words like that. And one of the sketches actually show only part of the building retained. But, it was there as, to be retained. So, yes it should’ve been factored in. There have been claims that it would be impossible to reuse because of asbestos in the window frames, but that’s not something that you necessary have to remove. You can just encapsulate it. And also, that there was no suitable use that it could be put to, but no designs were done either. So, there are various economic claims about its feasibility of retention, but they were never tested.

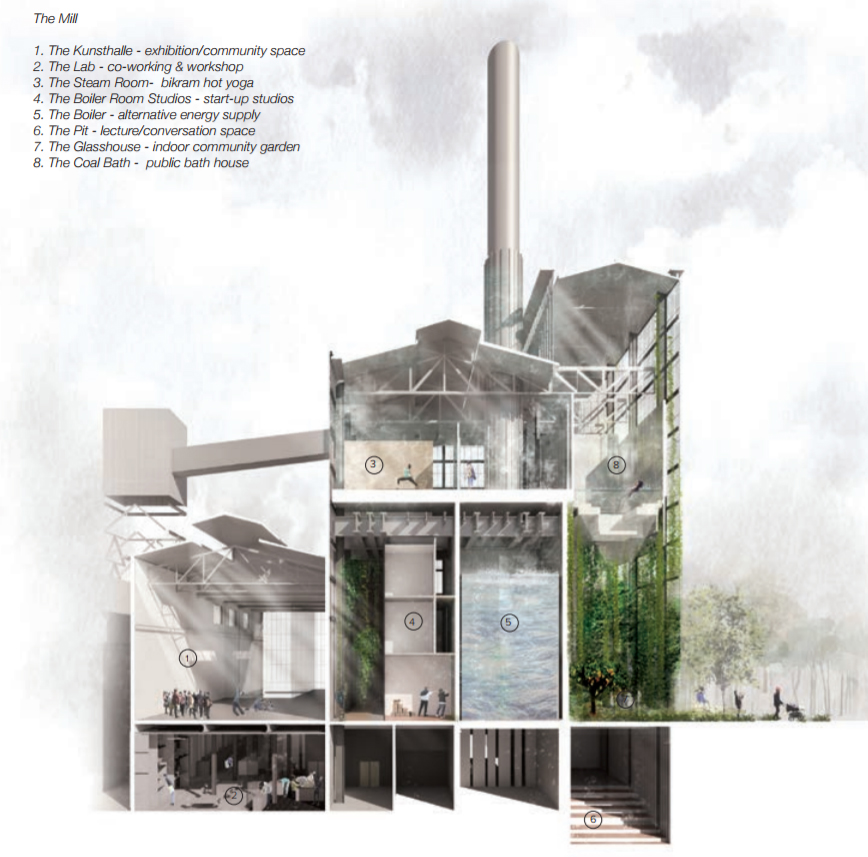

MS – One disadvantage of the community action proposing the demolition of this building, is that the community weren’t necessary presented with the possibilities for the site. There’s plenty of examples worldwide of industrial buildings, such as this one, being reused.

Indeed there is even a fantastic student project by Ariani Anwar from the University of Melbourne that looked at a possible adaptive reuse of this site.

A possible alternative future for the APM Boiler House as designed by Melbourne University Architecture student Ariani Anwar

RS – I don’t really know exactly what the local group thought, but the few bits that I could see on their Facebook page, what I heard from what happened at the meeting at the City of Yarra and from the quotes on their submissions to Heritage Council, that they really did focus on this one building as ugly, an eyesore and unsightly and must be demolished. I’m sure that that was because they just didn’t like the idea of a factory being across the road in the first place and were happy to see the whole lot go. They focused on this particular one, because it’s quite tall, and close to the Chandler Highway so it is quite prominent and quite obvious, a symbol of the site I suppose.

As a landmark it’s something that I’ve known since I was a child practically and sort of marvelled at. I never hated it. I always thought it was interesting and striking and memorable. I certainly always knew of it. But then, different people look at things different ways. And other people must’ve looked … driven past it a hundred times and thought, what an ugly monstrosity, I wish it was demolished. Being the most striking thing that you could really see of the site.

So, yes it’s a case of association. It’s ugliness by association. If it’s industrial, it must be ugly.

MS – Yes, there’s certainly other examples, Geelong being one of them, where an industrial building, such as the Ford factory, really becomes a notable landmark for the city or the community around it. And, no doubt there’s also a lot of stories from the generations of people who’ve worked in these places.

RS – A place like the Ford factory is a completely different set of circumstances because it was a major employer of a town that identified itself with the factory. Many locals worked at the factory and they had good employment conditions, so they had good associations with the building, which also has an architecturally designed ‘face’ to the street. Whereas, Amcor in Fairfield was surrounded by middle class housing. Probably very few people who lived there worked there, and anyone who lived there and remembered when it was working would only remember smells and smokes and steam and trucks and so on, and only had bad associations with it. So your appreciation of an industrial site will depend on who you are, where it is, who worked there, who didn’t work there, and what it did as well as what it looked like.

MS – You’ve currently got a petition out for those who feel strongly about retaining this building.

RS – Yes, even though the City of Yarra and the Minister have both said effectively you can demolish it and it may well be in the process of being demolished as we speak. I’m sure the developers are signing contracts now, but I thought I’d start a petition because the Minister’s saying no to heritage listing something despite the recommendations is not actually something that’s ever happened before. So it’s a terrible precedent to completely overrule Heritage Victoria and the Heritage Council, so I thought to make a protest to start a petition which would send an email to the Minister and the local Members just so that they knew that there were quite a few people who liked the building and didn’t want it to be demolished as opposed to the people who live in the immediate area who hate the building and do want it demolished. So, it’s more of a protest than any likelihood of actually saving it.

MS – Well good luck and thank you very much for your time.

To add your voice to the petition to save the APM Boiler House click here

For more information see the ‘Save the APM Power House’ Facebook page here

Architecture is for everyone

Contact Us

Feel free to contact us with questions or feedback:

Latest Post

- A crisis of trust February 10, 2020

- The Square and the Park. October 28, 2019

- Fixing The Building Industry – A Wishlist September 12, 2019

- 2019 NATIONAL CONFERENCE DAY 2 June 24, 2019

- 2019 National Conference Day 1 June 22, 2019

Leave a Reply